Private view: a studio visit to the hamaya archive

"Visiting a photographer's ‘inner-temple’, better known as their darkroom or archive, has always been a privilege. If one is fortunate enough to be invited in, one gains insight into the mind of the photographer – the outtakes, working contact sheets, good prints against less good prints, and the stories! All the ephemera that surrounds this profession has always been a passion of mine, and sharing this experience with you has brought back many fond and also exciting memories of my first visit to Hiroshi Hamaya’s home and archive in Japan."

Michael Hoppen

-

-

THE HAMAYA ARCHIVE

-

-

In 2004 I met the executor of Hamaya’s estate, who had been tasked with keeping Hamaya’s home in Ōiso and the neighbouring archive intact. This was no mean feat, as keeping an archive alive and functioning is a very complex task.

I knew a little about Hamaya’s life, but nothing prepared me for the wonderful surprises that lay waiting for me inside. Hamaya’s house was as he had left it. Simple and functional. The kitchen and the darkroom were neighbours. They led into a simple living and dining area, followed by the bedrooms and bathrooms which were each separated by sliding screens.

A garden full of blooming azaleas lay between Hamaya's house and the other small building that housed his archive.

The small darkroom had countless Christmas cards and well-wishing letters hung above the developing trays, from luminaries such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Ernst Haas, Richard Avedon and many others. Hamaya had been collegial to his fellow photographers and all the messages testified to his enormous generosity.

Despite some perished rubber hoses that connected the print washer to the water supply and some film spirals that had seen better days, the darkroom still felt alive. The subtle smell of D76 and hypo somehow lingered in the house, and it was hard not to reminisce about the endless hours in darkrooms I had spent when I practised photography.

-

-

Walking across the small garden during my first visit to the archive is a moment I shall never forget. There were five neat rooms lined along a narrow corridor. Each room was tidy and organised, and despite the yellowing of some of the paper, the place did not feel mothballed in the slightest. The first room held drawer upon drawer of negatives, each numbered, titled and dated in a neat hand.The second room contained the file prints and letters. Each letter was written out in Japanese and the reply to each was also there in Hamaya’s hand, in either Japanese or English!

The third room amazed me. Here were Hamaya’s Leica M3 and M4 cameras, lenses galore, handmade leather walking boots (all showing severe heel-wear), canvas camera bags, tripods, cable releases and all the myriad equipment that peripatetic photographers always seem to accumulate. -

-

-

Then came the room with magazines and books that his works had appeared in – countless copies of every known magazine that ever carried photography, and lines of books by Hamaya and his friends.

Finally there was a room with framed works that had been given to him over the years. Photographers were often known to ‘swap’ prints as a way of saying thank you, or impressing one another with a shot or a special print. These mementos thankfully live on at the archive.

We spent many hours going through the print files, discovering small gems and recognising the major works that Hamaya was famous for. Spreading these selections out on the tatami mat floor was our way of editing, a method I have experienced often when visiting artists in Japan. Large tables and large rooms are not as common, and space is always at a premium.

-

-

-

Every time I visit an archive or a photographer's home, the excitement of opening boxes that have maybe not been inspected for many years is always a thrill. The discoveries and learning curve is always more pleasurable when working in the artist's own environment, and recognising their oeuvre and their systems is an integral part of finding out about their individual photographic practices.

My only regret in this instance is that I never managed to meet Hiroshi Hamaya.

-

Featured works by Hiroshi Hamaya

More works available -

-

-

-

Featured works by Hiroshi Hamaya

-

Hiroshi Hamaya, Boys singing to drive away the harmful birds, Niigata, from the series "Snow Land" , 1948

Hiroshi Hamaya, Boys singing to drive away the harmful birds, Niigata, from the series "Snow Land" , 1948 -

Hiroshi Hamaya, Recreational Field, Shanghai, 1955

Hiroshi Hamaya, Recreational Field, Shanghai, 1955 -

Hiroshi Hamaya, “Live long Chairman Mao”, Beijing, China, 1956

Hiroshi Hamaya, “Live long Chairman Mao”, Beijing, China, 1956 -

Hiroshi Hamaya, Precious metal dealer, Guangzhou, China

Hiroshi Hamaya, Precious metal dealer, Guangzhou, China -

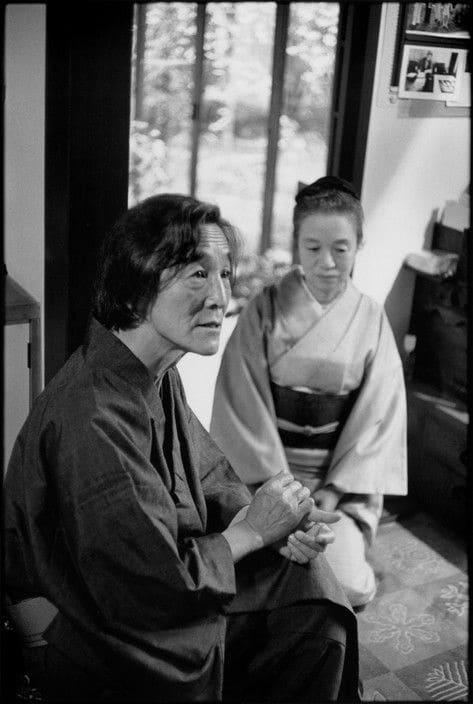

Hiroshi Hamaya, A woman performing the tea ceremony

Hiroshi Hamaya, A woman performing the tea ceremony -

Hiroshi Hamaya, Men moving sacks, China, 1955

Hiroshi Hamaya, Men moving sacks, China, 1955 -

Hiroshi Hamaya, The demonstration of students from 'Chronicles of Grief and Anger.', 1964

Hiroshi Hamaya, The demonstration of students from 'Chronicles of Grief and Anger.', 1964 -

Hiroshi Hamaya, The United States-Japan Security Treaty Protest, Tokyo, 15 June 1960 From 'Chronicles of Grief and Anger.'

Hiroshi Hamaya, The United States-Japan Security Treaty Protest, Tokyo, 15 June 1960 From 'Chronicles of Grief and Anger.' -

Hiroshi Hamaya, Tokyo, 10 June 1960

Hiroshi Hamaya, Tokyo, 10 June 1960 -

Hiroshi Hamaya, Taxis waiting for customers, Ginza, Tokyo, 1934 , printed 1960

Hiroshi Hamaya, Taxis waiting for customers, Ginza, Tokyo, 1934 , printed 1960 -

Hiroshi Hamaya, Sukaya Hot Spring, Aomori Prefecture, 1957

Hiroshi Hamaya, Sukaya Hot Spring, Aomori Prefecture, 1957 -

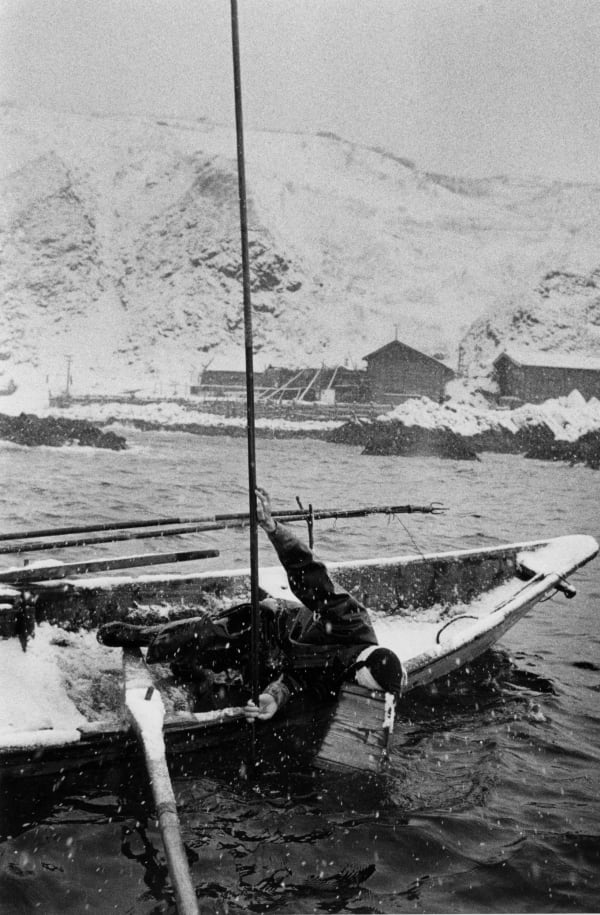

Hiroshi Hamaya, Fisherman Spearing Fish, Hokkaido, Japan, 1957

Hiroshi Hamaya, Fisherman Spearing Fish, Hokkaido, Japan, 1957

-

-

We hope that you have enjoyed our virtual offer and that you will

to us if you have questions or would like to know more.

Click here to view our full offering