-

Photography enables one to show, liberate and develop one’s sensibility. […] At the moment of pressing the shutter you had to keep the image - let your emotion, discovery and visual surprise flow - the moment had to be kept in your head. That’s what I call developing one’s visual memory. - Kati Horna

-

These pictures, taken and printed by Kati Horna after she settled in Mexico in 1939, illustrate many of the most distinctive hallmarks of her photography. Oda a la Necrophilia was conceived by Horna as her first contribution to the ‘Fetiche’ section of S.nob magazine, a short-lived but influential late Surrealist publication edited by the cult writer Salvador Elizondo.

-

-

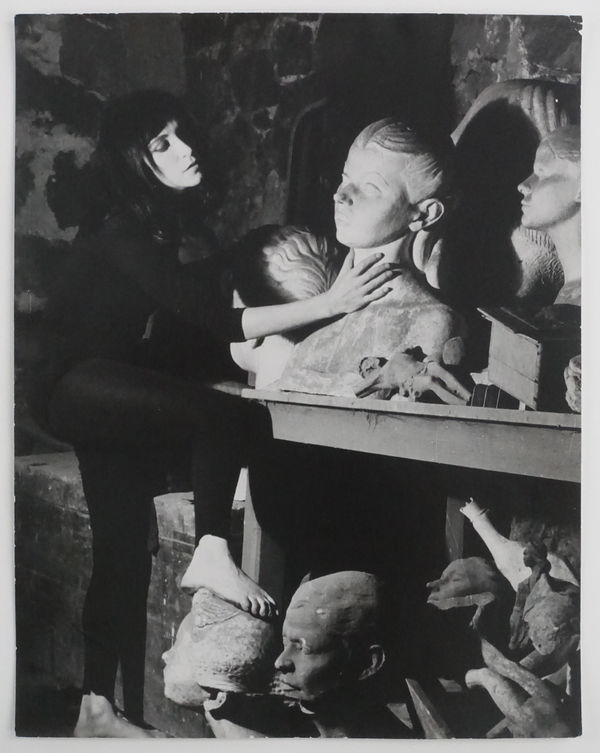

Kati HornaLeonora Carrington, 1957Vintage silver gelatin printPaper size: 25 x 20 cmSigned and titled in pencil, annotations in Spanish in black pencil verso

Kati HornaLeonora Carrington, 1957Vintage silver gelatin printPaper size: 25 x 20 cmSigned and titled in pencil, annotations in Spanish in black pencil verso

Artist estate stamp verso -

Kati HornaPortrait of Leonora CarringtonVintage silver gelatin printPaper size: 17.7 x 12.8 cmSigned in pencil verso

Kati HornaPortrait of Leonora CarringtonVintage silver gelatin printPaper size: 17.7 x 12.8 cmSigned in pencil verso -

‘SHE WAS AN ARISTOCRAT BY INHERITANCE, AN ANARCHIST BY CONVICTION, A SEDUCER BY NATURE AND A WANDERER BY VOCATION…’- JUAN LUIS DÍAS

-

-

-

-

Kati HornaSubida a la Catedral, Guerra Civil espanola, Barcelona, Espana, 1937Vintage silver printPaper Size: 25.2 x 20 cmSigned and dated verso

Kati HornaSubida a la Catedral, Guerra Civil espanola, Barcelona, Espana, 1937Vintage silver printPaper Size: 25.2 x 20 cmSigned and dated verso -

The violence and injustice that forced Horna to take flight across Europe informed her attitude to photography, which remained socially engaged without conforming to the prevalent social documentary style. Horna’s bold eye for graphic juxtaposition and her urgent concern for recording political brutality at a personal level won her commissions throughout the turbulence of the 1930s. It was at this time that Horna cemented her friendship with the legendary photographer and Magnum founder Robert Capa, who she met first as a teenager in Hungary, before encountering him again in Paris and later Spain, where they spent time together documenting the Civil War.

‘Mexico City had one million inhabitants, a blue sky, and you could see the volcanoes. I was a magazine photographer and got home at midnight […] I was 27 years old, and I often walked home because the night was so beautiful […] You could live anywhere you wanted, where your friends were; Remedios (Varo) was five minutes away and so was Leonora (Carrington), and I was here.’ - Kati Horna

-

Kati HornaUntitled. Cuidad de Mexico, 1949Vintage silver gelatin print22 x 19.5 cm

Kati HornaUntitled. Cuidad de Mexico, 1949Vintage silver gelatin print22 x 19.5 cm

Signed in pencil verso -

Horna had long considered photography a vehicle for independence, giving her a political voice through which she could express radical ideas at a time when such opportunities were extremely limited for women; Her Spanish pictures display an acute concern for the experience of women at war and their changing role in modern society. This preoccupation with women's representation is further developed in some of the most celebrated series of her Mexican career, prominently illustrated in publications including Mujeres: Expresión Femenina (Women: Feminine Expression) and the experimental journal S.nob (above).

-

-

Enjoying the new creative freedoms afforded by working for the avant-garde press, Horna was able to explore using photography as a tool for illustrating psychoanalytic principles, which had fascinated her since her youth. In 1940 she visited the International Surrealist Exhibition organised by André Breton in Mexico City, and developed an intellectual affinity with the movement. Whilst she was not interested in pursuing closer ties with members of the group in Europe, Horna welcomed the opportunity to collaborate with sympathetic exiles like Carrington and Varo, and together they cultivated an independent and distinctly female Surrealist vision from abroad.

-

Kati HornaEscena de Teatro Gironella y Jodorowsky, Mexico, 1962Vintage silver gelatin printPaper Size: 23 x 19 cmSigned in pencil verso

Kati HornaEscena de Teatro Gironella y Jodorowsky, Mexico, 1962Vintage silver gelatin printPaper Size: 23 x 19 cmSigned in pencil versoHorna’s 60 year sojourn in Mexico testifies to a life devoted to image-making. From architectural landscapes to uncanny montages, her relentless curiosity and technical acuity inspired a body of work inextricably bound up with the progress of women and the avant-garde over the course of the 20th century. Horna’s indomitable attitude is summed up in a mantra fondly remembered by her colleagues and students: ‘The camera is not the obstacle, it is one’s self!’